Joey L’s Signature Look

February 6, 2013

“Joey L.” is the nom de lens of 24-year-old Canadian born photographic phenom Joey Lawrence. His meteoric career took off in 2004 when he was still using a point-and-shoot camera, and like so many of us at the start, snapping away at rock musicians who could barely pay for replacement guitar strings, much less the flashy images they needed to get bookings. Still, it was great practice for a fledgling shooter. Four years later, Joey L.’s distinct, evolving style landed him an important shoot—and an image that helped launch the chart-busting Twilight film series. That now iconic poster, featuring brooding co-stars Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson, is a remarkable blend of menace and a sort of luminous sexuality. Lawrence’s acute instinct for creating mood and the etched, painterly lighting style he drew on to capture that effect, got the immediate attention of a prestigious client list who would soon find their way to his studio—cablecasters such as Verizon, Nickelodeon, A&E, the History Channel and FX, along with mainstream heavy-hitters Smirnoff, Coca-Cola, Pennzoil, Kawasaki, Forbes magazine and more.

“Joey Lawrence,” writes photographic blogmeister David Hobby (Strobist.com), “is young, technologically literate, ambitious and already playing the long game. He is the future of photography. Get used to it.” That gushy testimonial keynotes Hobby’s foreword to a lavish and yet amazingly utilitarian new Amphoto release, Photographing Shadow and Light, subtitled, Inside the Dramatic Lighting Techniques and Creative Vision of Portrait Photographer Joey L.

All Photos by Joey Lawrence, “Portrait of Rufo”

An Exception to the Rule

The latest hotshot wunderkind photographers aren’t traditionally given to formally packaging the nuts-and-bolts details of their craft or their creative manifestos. The preference seems to be photo magazine interviews and—for a select list—the occasional radio or television appearance. Lawrence himself has been featured on NPR and NBC’s Last Call with Carson Daly, but, in the matter of books, he appears to be an exception to the rule. He likes to share with other shooters, so he put his story and many of his “secrets” in book form. Photographing Shadow and Light is a frank explication of his personal vision, the history of his private, self-taught learning arc, and, most importantly for his fellow photographers, detailed, behind-the-camera accounts of 15 dramatic shoot scenarios—both commercial assignments and personal work.

The signature look that defines most of Lawrence’s photography is his heavily stylized lighting, both indoors and out. Each mini-chapter in the book is devoted to a single photographic problem and its solution. They all begin with a little menu he calls the “Camera Bag,” where he lists his gear choices for that particular shot—camera, lens and, in nearly every case, an electronic flash unit, its power source, and a rundown of accessories for light modulation. His favorite kit seems to revolve around Profoto packs and heads, frequently battery powered for location exteriors, and a 69-inch Elinchrom Rotalux Octa. He selectively puts in accent lighting with flat reflectors, additional heads, sometimes capped with grids or gels or smaller softboxes, continuously augmenting a setup until he gets the look he’s after. He calls it his “additive” approach to lighting, and it’s often a cross between the drama of an Old Masters painting and that distinctive cinematic texture of vintage movies—the Gregg Toland and James Wong Howe eras. These influences are indisputably woven into his personal style. The look can sometimes seem a little overwrought, particularly in the work he does for commercial clients, but it creates a distinctive sparkle that makes his ads jump off the page. Especially helpful on the lighting setups in this book are schematic diagrams to ease the guesswork for a reader trying to visualize placement of light sources relative to camera and subject.

Key among Joey L.’s skills appears to be his adaptability to a broad range of rugged exterior situations. My personal favorite image showing Lawrence himself doesn’t appear in the book; it’s him posing for a quick portrait in some chilly windblown outback in South America, holding his treasured Octabox and its light stand just off to the side while someone else—presumably his assistant—took the shot. It’s understandable that he’d be tapped by art directors for the creative and technical flexibility this portrait illustrates. One case in point: a series of promotional shots for a History Channel reality show, Ice Road Truckers, later renamed IRT: Deadliest Roads. His shoot for this series is a featured chapter in Photographing Shadow and Light, and deals with the technical problems inherent to working with high-end camera and lighting equipment in the harshest conditions imaginable, from the desert to the arctic. For photographers, the marquee image in this chapter evokes that shot of Lawrence with the handheld Octabox: this time it’s an assistant, powerpack slung on his back, holding the same Elinchrom and lightstand aloft to capture a tough-looking trucker riding his running board beside a steep precipice in the mountains of Bolivia.

“Silverstein: Victory”

Far-flung Places

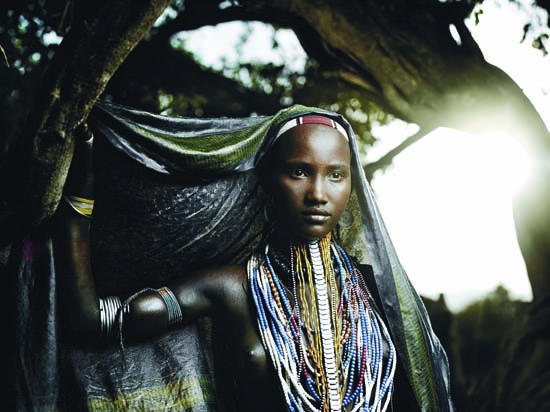

Lawrence’s work with reality show cast members draws on another of his skills: working with subjects who are less than comfortable in front of the camera. Despite their TV star cachet, the cast of reality shows such as Deadliest Roads, Mudcats (about Oklahoma catfishermen), and the wildly (if inexplicably) popular Pawn Stars, are not professional actors, accustomed to the camera, nor probably imaginative enough to grasp a photographer’s directions in an advertising shoot. Lawrence’s easy-going style with these subjects and simple ploys, such as using familiar props with his subjects, puts them at ease. He’s achieved similar results with the indigenous natives who populate what is probably his most serious work—the personal fine-art portraits he does in far-flung locations that range from the tribal lands of Ethiopia to Hinduism’s holiest city, Varanasi, India, to the volcanic highlands of Vanuatu in the South Pacific.

Several of the photographer’s native portrait sessions are represented in Photographing Shadow and Light—all stunning samples of this genre of travel photography. They’re extraordinary, in part, for his fearless approach to using hi-tech, sophisticated equipment in rough, unpredictable exteriors—gear such as Phase One camera backs and his omnipresent Profoto packs and heads. The results are elegant, superbly detailed portraits that celebrate the strange and beautiful inhabitants of these exotic stretches of our planet, and Lawrence seasons his technical solutions in these situations, with anecdotal recollections of his moments with some rare and fascinating people.

In a chapter devoted to style, Lawrence makes much of the importance of a photographer adding his personal stamp to his work. “Ultimately,” he insists, “the photographic process should say something about the photographer as well as his subject.” Whether or not you buy into that idea, it’s clearly what Lawrence’s unique techniques and craftsmanship have done for him. In Photographing Shadow and Light, he provides you with a rich and accessible guide toward achieving that same goal on your own.

Writer and veteran commercial photographer Jim Cornfield (www.jimcornfield.net) is Rangefinder’s resident book reviewer and a regular contributor (see “Hands on History” in this issue, page 92).